While reading the wikipedia article on married names for my last blog post, I came across a reference to the “Lucy Stone League,” which was founded in 1921 and was all about campaigning for a woman’s right to keep and legally use her name after marriage. This led me to read up more on Lucy Stone, one of the first women to do so.

And she was awesome!

Lucy Stone was born in 1818 and from a young age vowed support herself and not marry, because she saw how being dependent on some dude was not the greatest for her mom, her aunt (whose husband abandoned her), and other women in her community. To this end, she struggled to pay her way through college at Oberlin through teaching, although for most of that time she was paid a “woman’s salary,” significantly less than what her male colleagues made. She started making her living as an abolitionist and women’s rights orator, and that’s how she met Henry Blackwell.

Henry asked her to marry him, and she was all, “Listen, guy, I like you, but not enough to give up my property, rights, and identity to you, you know?” Valid point, girlfriend. But THEN Henry was like, “No, Lucy, even though our entire society has told me my entire life that I am superior to you in every way I don’t buy it. We should be equal partners, and I care enough about you as a person to make that happen.” I’m paraphrasing obviously but ~swoon~.

Seriously, that is like the most romantic thing ever. Henry thought that marriage should be a partnership that let each spouse succeed in ways they couldn’t alone–to prove it he organized her lecture tour in 1853. When Lucy finally agreed to marry him, they also agreed to split all expenses, and keep their own separate property if they split up. Blackwell also agreed that, since women are the ones most burdened by “the results of intercourse,” it would be up to her “when, where, and how often she became a mother.” HOLY CRAP THIS WAS 1854 YOU GUYS!!!

Anyway, they got married, Lucy Stone kept her name–or tried to. Even though there was no specific law saying she had to take her husband’s name, she often had trouble paying taxes, buying property, and doing other public-document-type things because the clerks would insist that she had to use her “real” name.

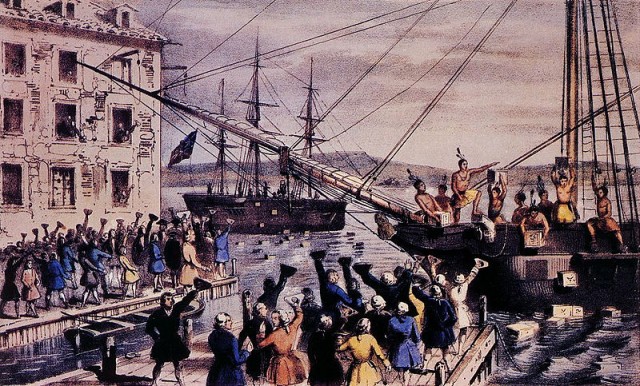

Also once she refused to pay her property tax because it was 1858 and women couldn’t vote. She mailed it back to the county clerk with a letter explaining that it violated America’s founding principles.