Title: The Awakening and Other Stories

Author: Kate Chopin

Challenged in: Oconee County, Georgia

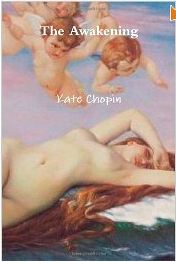

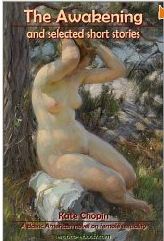

For: “the cover of the book… shows a painting of a woman’s bare chest and upset the patron”

So this morning I got out my copy of The Awakening (it still has a Lord of the Rings bookmark in it from senior year of highschool!), all ready to comb through it once more for the sexy parts or the parts glorifying suicide or the (multiple) times when Edna is a terrible mother. So you can imagine my delight when I rechecked my list and saw that this book is another one that was challenged for the cover. I’m really pleased to not have to read any part of The Awakening again, since I didn’t really enjoy it the first time!

So, let’s talk about covers and breasts and how upsetting they are. I couldn’t find any reliable news articles about this incident, so it’s hard to know what cover Oconee County is objecting to. Since this book was first published in 1899, there have been a lot of editions with tons of different covers. I did a search on Amazon and came up with at least three possibilities for you: (behind a cut to protect you from painted breasts)

I’m betting it was probably not the Kindle edition, but I’m sure there are lots of other options for bare-breast Awakening covers that my cursory search didn’t find. All of them will be paintings like the above. The majority of the covers I found just pictured Kate Chopin or random ladies of the 1890s by the sea.

The patron who objected to this book apparently only saw it because it was part of a Banned Books Week display. Depending on the level of nudity (the last two, for instance) I can see myself hesitating before putting the book on display, depending on the display’s location and my individual library. I would probably ultimately go ahead with it anyway, since the book is a classic and the paintings are no more explicit than any you might see in a public art museum, to which children are regularly taken on field trips. Sure, they might giggle a little as they pass by, but I don’t think it’s doing a lasting damage. Though paintings like this are sometimes challenged for being pornographic, they’re so far removed from porn in purpose and style that I’m not even really going to talk about it because the arguments are boring.

Also, if we’re removing books from the library based solely on covers, I have some suggestions.

Previously: We’ll Be Here For the Rest of Our Lives

Next: Great Soul: Mahatma Gandhi and His Struggle With India

Which materials don’t belong in a library? Books, like Lolita, that describe the sexual relationship between a middle-aged man and a 12-year-old girl? What if the descriptions were graphic? What if it were a picture book? A magazine? A graphic but fictional movie? A documentary of actual pedophilia? A home movie made by a pedophile who rapes and tortures children? Where would you draw the line?

Also, why should patrons wanting to challenge a book have to read it first? What if it were a 1,000 page memoir on kidnapping and molesting children? Doesn’t that assume the material isn’t really that offensive? We don’t, for example, require lawmakers to read a bill before opposing it. Why should library patrons face a higher standard when challenging potentially revolting books?

We absolutely should force lawmakers to read a bill before opposing or approving it! I’m in favor of decisions–especially important ones that affect so many people like laws or restricting access to library materials–being as informed as possible. Ignorant decisions based on preconceived notions are no better than playing rock, paper, scissors to decide something.

Libraries choose every inclusion in their collection for a reason. The Awakening is a famous classic novel, one of the first to focus on women’s rights, and is read in many schools, which are all good reasons for the library to own it in this case. Some of the examples you list would not be included in a public library collection for various reasons, like not enough perceived demand. Lolita probably would be included since it is often listed on “Best Books of the 20th Century” lists put out by Time Magazine or Modern Library, is one of the best examples of an unreliable narrator, and has generated so much controversy that it is even still in high demand among curious readers. Individual public libraries have their own collection development policies (usually available on their website, if you’re curious) that are catered to their specific community. Obviously there will still be inclusions that won’t make absolutely everyone happy, but communities and their needs are diverse, and neglecting to carry a classic novel because someone objects to the art on the cover is a disservice to the many people who would like (or, in my case, were forced) to read it.

Why are you so scared of books you disagree with? Are you afraid they’ll make you change your mind?

Surprisingly, I don’t “disagree” with child pornography because I am secretly afraid of turning into a pedophile.

But what I would like to know is, where would you draw the line? Obviously libraries have policies explaining where they think the line should be. Surely you have an opinion too.

So, since you didn’t bite on my last hypothetical, how about this:

Imagine a rogue, free-speech-loving librarian who chafes under the “community demand” requirement. After all, materials favored by 5% of the national population (15 million people) might appear in 0% of libraries if the constituency isn’t big enough in any particular area. To rectify this injustice, she (with appropriate legal blessings) fills her library with materials favored by the margins of society, so they at least have one place to go. Is there anything she could stock that you would challenge? I trust your imagination better than mine to account for the breadth of (vile) available materials. If there are materials you might challenge, what factors would you consider in deciding whether to challenge them? Should there be different standards for written, picture, and video materials?

In short, where, if ever, would you (not other people) draw the line?

This reminds me of two studies I read in grad school to see what librarians would do when someone asks them for information about how to build a bomb and how to freebase cocaine respectively:

Hauptman, R. (1976) Professionalism or culpability? An experiment in ethics. Wilson Library Bulletin, 5(8), 626-627.

Dowd, R. (1990) I want to find out how to freebase cocaine or yet another unobtrusive test of reference performance. The Reference Librarian, 11(25)

The researcher found that the majority of public librarians approached at least tried to help him find the information to the best of their collection’s abilities. As a librarian, you don’t know why patrons are seeking the information they’re asking you for–Are they writing a book about a drug addict? Are they wanting to better understand a family member who is suffering from addiction? Are they a library science researcher? Are they just curious?

Of course, these studies were both done before the internet could provide both sets of information much easier for free. The Internet has definitely changed the way library purchases are made–it no longer seems necessary to have access to any potential piece of information anyone might ask for. If you can’t find a book on it, try the internet!

I know you’re trying to get me to say that some things are too objectionable while other things are okay, but those decisions have to be made on a case by case basis. For any material that exists, I can think of a reason why some library somewhere might collect it. For instance, many different kinds of social science researchers might want to compare pornography from different decades or for different audiences. When a librarian collects a material, they’re not saying “I agree with this.” Most libraries own a copy of Mein Kampf, but that doesn’t mean the librarians or their community are Nazis. My personal morals don’t enter into it at all–when you’re collecting you’re attempting to create an unbiased resource for the community, which will certainly contain individual books with which you don’t agree.

Are you asking whether, once a book is in the collection already, I would ever challenge it? I have before, when I thought it was cataloged in the incorrect section. For removal from the library entirely? No.

Tackling these in order:

1. keep (it’s a classic),

2. still keep (good descriptions are good),

3. keep but shelve under adult graphic novel (because pictures!),

4. keep? (most libraries don’t have much of a magazine collection, so this is a null point),

5. keep? (fewer and fewer libraries have movies at all, much less objectionable ones, so probably also a null point),

6. keep (documentaries are useful educational tools),

7. discard (what would someone’s home movie be doing in a library?).

And patrons should at least glance through something they want to challenge for the same reason you should look at your food before claiming someone spat in it; to see if they have any point whatsoever to make.

As to your example, I’m starting to see a pattern. You really have a thing for molesting children, I notice. Might want to get that looked at.

And on a side note, any lawmaker who passes or opposes a bill without reading and evaluating its full contents is criminally neglecting the duty to which we elected his sorry ass. Recalls all around! 🙂

Obviously, I was hoping the example of pedophilia would provoke indignant condemnation. If you like, replace it with whichever content you find most objectionable. And by “home movie” I meant a video diary of the acts made by the perpetrator, kind of like a reverse, twisted, video “Diary of a Young Girl” (which some libraries carry).

To the issue of mootness, many of my examples would be prohibited under federal law anyway. I nonetheless take poorly your objections in numbers 4 and 5. For the purpose of the hypothetical, it should suffice that a library could stock the material (legal issues aside). Whether many would is irrelevant.

Finally, since you OKed the pedophilia, what about materials that may facilitate or provoke violence? For example, some libraries keep “The Anarchist Cookbook,” which contains recipes for homemade bombs. Would you challenge it? What if you knew, empirically, that the only person(s) to check it out used it to make bombs and kill people? Would any link between the book and violence be enough to have it removed? What about a book that insulted Islam in a predominantly muslim neighborhood, and that had the demonstrated potential to cause violence?

Other threats to people might exist in a library. Legal issues aside, if the next Bradley Manning sent his local library secret military plans that were published on the library website, would you oppose them?

If all you’re looking for is a gimme reaction resulting in a simplistic solution to a complex problem (and in an Internet comment section, no less), then I’m happy to tell you that there’s a word for what you’re doing: trolling! 😀

I do like your examples, though. Particularly that subtle switch from the question of challenging a book to “OK[ing] pedophilia” (nice ignoratio elenchi, by the way, and will someone think of the children?!). As a friendly word of advice, rhetorician might not be your ideal career choice in the future.

Let’s look at your example. As someone who happily perused The Anarchist Cookbook (and its various chemical, electronic, and software-oriented offshoots) in his teenage years, I’d be reticent to challenge it unless it was shelved in the children’s or teen’s sections, and then only because it’s likely to be misused as a tool for braggadocio or rebellion rather than the handy guide to home experimentation that it actually is. Personal thing, really.

In any event, that’s a collection development question for the library in which the work in question is found as to whether its contents violate their standards. You’re attempting to put forth the fallacious argument that the intent of the borrower in selecting his or her library books is (or should be) collected and evaluated by the librarian(s) in order to formulate collection policy. This intrigues me. If that were the case, should not the DMV clerk be asking you about the reasons you’ll be needing that driver’s license? After all, if you had it in your mind to do some illegal drag racing, it wouldn’t be a good idea to issue you one. Or, closer to home, how about the garden center clerk at your local Home Depot? Surely he shouldn’t be selling you that fertilizer without first checking whether it’s going into a bomb. Something I’m sure you’ll be only too happy to tell him if that should be your plan, yes?

Most laughable of all is your last example there, I think. Secret military plans on a library website? Have you mistaken your county branch library system for Wikileaks, I wonder? Or librarians for social anarchists simply itching to publish that which society and the law tell them that they should not?

Legal issues aside indeed (and I’m not willing to grant you that sort of evasion wholesale, please mind), I put this to you as someone who deals with (and evaluates others’ ability to deal with) web content professionally; have you spent much time on any library websites? Point out to me, if you would, some examples of areas on said sites where the public can freely post content. These are not, as a general rule, bulletin boards freely open to the uninformed masses to fill with their soapbox rants and soap opera drivel. These are small affairs, at a minimum disclosing location information and hours of operation. Generally run by the county’s central I.T. department (where funding and organization are present and allocated sufficiently) or by the one or two people in the system or individual library with the necessary technical skill and credentials to do so (in the more common instance where funding, etc. are not so freely available). Updates are frequently infrequent, content often limited to simple event listings and (if funding permits) some utility where patrons can check their balances and perhaps search the catalog.

I support libraries wholeheartedly (even to some degree in spite of my heavily libertarian leanings with respect to government’s social and fiscal mandates), but even I who would like to see them have more presence and utility within our communities am not so silly as to mistake them for the bastions of anarchy and sedition you seem to imagine them to be. Your ability (perhaps even your right?) to challenge the contents of a library collection exists for two reasons: [1] to help the library correct errors in the organization and shelving of the collection’s contents (which are bound to happen) and [2] to help highlight *potential* problems in its collection development policy. There’s no question that there are materials not well suited to a particular collection in a particular community–Hindi language texts in a predominantly Hispanic neighborhood, for example, would serve few and use up funding for more relevant works. But you won’t find any universal rules that apply to a given work’s appropriateness for all collections. Such rules don’t exist.

Once again, it sounds like you’d really prefer the library and its librarians to do the policing and the parenting in your community, rather than the officers (who are paid more to do so) and parents (who make the conscious decision to take on the job) whose responsibilities those are. Libraries are for providing access to information. The responsibility for what you do with that information rests, as it always will, on you.

Thanks for playing!

Admittedly, I meant to write that you OKed child pornography, not pedophilia (per your answers numbered 3 and 4). Of course, I do not suggest you are OK with the act of pedophilia, just that you would OK (not challenge) the presence in a library of real pictures of pedophilia in a book or magazine. As such, my point was not an ignoratio elenchi, but rather gets to the heart of the issue: where to draw the line.

Secondly, you claim as “fallacious” my idea that we might restrict the availability of certain things depending on their intended use. I suggest we do this all the time. Expanding on one of your examples, if a driver is found drinking and driving his license is usually automatically suspended out of fear he will drink and drive again. Felons aren’t allowed to possess firearms because we’re afraid they will use them to commit crimes. Access to many hazardous chemicals is limited to those with special licenses to ensure they are not misused. In fact, some states even limit the amount of certain cold medicines that can be purchased because they can be used to make methamphetamine. Really, more broadly, this “fallacious” principle underlies all licensing regimes.

Thirdly, you ridicule my idea that secret military plans could be placed on a library website. To be clear, I mean documents uploaded by the library itself as part of an online collection, not message board comments. Imagine someone found Russian military plans from the 1990s as part of internal Kremlin documents of keen interest to historians (Soviet files certainly exist in some U.S. libraries). Since those documents may well not be legally protected in the U.S., should the library scan them and make them available online? What if the plans involved technical specifications of advanced surface to air missile systems? Is this just a beefed up version of the bomb-making instructions in The Anarchist Cookbook?

Finally, if you’re just going to defer to the library’s decision anyway then you would not challenge any of my hypothetical materials, because I assume they’ve been shelved. Rather, the only reason you can hide behind “well, that would never happen” is because libraries do what you refuse to. They censor their collections. They reject materials because they are offensive to the community or may incite violence.